I suppose writers had it pretty bad three or four thousand years ago, when chisels and stone tablets were the only writing implements to be had. We must have breathed a collective sigh of relief when parchment and ink came around, and then (for the handwriting-impaired among us) the mechanical typewriter. And for the last thirty years or so, we’ve been able to write and revise on-screen with word processors, instead of having to retype everything anew with each draft. “Progress,” wrote Robert Heinlein, “isn’t made by early risers. It’s made by lazy men trying to find easier ways to do something.”

Then God bless the lazy men and women at Literature and Latte, the makers of Scriviner. They’ve spent the last several years trying to perfect the task of writing, and they’ve come damn close. At this point, you may as well go dip your quill in ink and grab a length of foolscap as use something as antiquated as Microsoft Word. Word is fine for shorter-length stuff (anything up to ten thousand words or so). It’s got a great revision-tracking system, and since it’s the standard format for editors and agents, you’re going to be using it to share revisions at some point. But I shudder at the thought of trying to use it to actually write a full-length novel.

Folders and Sub-documents

One of the things that Scrivener does an amazing job of is letting you break your manuscript up into folders and sub-documents. With Word, you either put everything into a single file (which makes navigating difficult) or you break each chapter or scene up into a separate document (which makes it hard to join it all together again).

With Scrivener, you create a ‘project’ for each manuscript. The project is like a miniature, self-contained file system. You can create folders and subfolders to organize all your various scenes, chapters, and notes, which means that you don’t have to wrangle the herd of separate-but-related Word documents that make up your manuscript. I like to have a folder for each major draft of a novel, with each chapter in a draft broken out into a separate document. That makes it easy for me to navigate between chapters in my current draft and see the word count for the chapter I’m working on. I can also easily find a particular chapter in an older draft if I want to resurrect some bit of description or dialog. Some people break their manuscripts down even further, with a folder per chapter and a document for each scene in the chapter. Scrivener will let you do things like search and replace or word counts across an entire draft, so it never feels like breaking your manuscript up into sub-documents ever becomes ‘too much.’ It’s really just about whatever is most convenient for you.

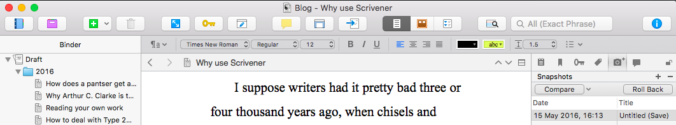

Snapshots

Snapshots are a way of keeping older versions of a particular document around in case you want to go back to them. Snapshots are astonishingly, wonderfully, awe-inspiringly amazing, and once you get used to them, you won’t be able to write without them. I create a snapshot of whatever I’m working on at the end of each writing session. That gives me the freedom to hack apart a chapter and put it back together again without worrying about losing my work. You can restore a document back to a particular snapshot if you want, or you can view the differences between an older snapshot and the current version to see what’s changed. Some people even use snapshots as a way to work with writing partners or editors, by taking a snapshot of their original version and then comparing with the new version.

Compiling

Compiling is at the heart of what makes the project-based, folder-and-document structure of Scrivener work. You can keep your manuscript broken up into whatever chunks make the most sense to you when you’re writing—scenes, chapters, sections—and when you’re ready, you compile them all back together again for output to a printer, exporting to a Word doc, or even generating a ready-to-read Kindle ebook. Scrivener can automatically add chapter headings, page breaks, and title pages to make the output look exactly the way you want.

There’s another great benefit to compiling. After my years of using Microsoft Word, I’ve gotten used to good old Times New Roman. More editors are accepting drafts in roman type, but some still require fixed-width fonts like Courier. I like 1.5 line spacing with a little extra between paragraphs, but submission formats often ask for double-spacing. In a regular word processor, you’d have to constantly change back and forth between different options in order to generate a printed or digital copy with particular formatting.

In Scrivener, the font, spacing, and styling that you use in the editor have nothing at all to do with how it gets compiled. If I need traditional typewriter-style printouts, I can choose that option when I compile for printing, and the editor never needs to know that I’d been working in mushy old Times New Roman the entire time. You can set up headers, page numbers, fonts, and spacings to exactly the format that a picky journal or magazine asks for, and then re-use those settings whenever you’re ready to submit.

Scrivener can also compile your project to the Kindle ebook format. I’ve written before about how useful it is to read your own work in a ‘realistic’ setting. With Scrivener, it’s easy to take the latest draft of your manuscript and export it to your Kindle (or the Kindle app on iOS/Android) and read it over. While I don’t suggest that you use its output format for actual self-publishing—you’ll want an app that’s designed specifically for that—the Kindle output is a great way to share with friends, family, and beta readers.

The details

Scrivener does a lot of little things well, too—it has an excellent tool for setting word count goals, which I use for making sure that I’m on track to get to a particular manuscript length by a certain date. It has a solid ‘distraction-free’ composition mode, and great tools for outlining, cork-board-style organization, and note-taking. It can back up your entire project to a timestamped zip file, which you can easily back up to an external drive or cloud file service so that you can go back to older versions even if you really cock things up.

There are probably a dozen other great Scrivener features that I hardly use but other people will swear by. It does a good enough job at everything so that I’ve never felt like I was leaving anything behind by abandoning Microsoft Word. I even have a Scrivener project for blog posts, so that I don’t have to worry about the internet eating my latest draft. I still have to do a little formatting once it gets into WordPress, but all of the basics like bolding/italicizing work properly with a simple copy-paste.

Best of all, Scrivener is reasonably-priced: $40 for either Mac or Windows, and you can sometimes grab it on sale for half that. Do yourself a favor and check it out. I’ll bet that after a week or two using Scrivener, you’ll look back at the bad old days of regular ‘word processors’ and wonder how you ever got anything done.

from the I-made-my-word-count-for-the-week-dept.

Leave a Reply