First drafts are a pain in the ass. They are, by far, the hardest thing about writing. There’s a blank page, there’s you, and there’s some idea you’ve got for how to turn that empty whiteness into a full-fledged story.

There are a few important rules for first drafts. First and foremost is always that first drafts suck. You have to turn off your inner editor and just write something. The second rule is write what you have. Don’t spend lots of time trying to come up with ideas, scenes, characters, plots, settings, or anything else that doesn’t come naturally. Just keep going and finish that draft.

Of course, you do have to have something, or it’s not a story. So what do you need to have by the time you finish that first draft?

First, you need a beginning and an ending. Every story has an inciting incident (which isn’t necessarily in the opening chapter or scene). The beginning has to begin this story, not a different one. Similarly, your novel has to resolve itself somehow, in a way that’s faithful in some way to the story you’ve told. Just like how combining any subject with any verb creates a complete sentence, putting together a beginning and an ending creates a story.

Second, you need enough detail for the core of the story to be told. If you say “boy meets alien and eventually helps him return to his spaceship,” then you have a beginning and an ending, but there’s no detail. If you listed out the core scenes of your story (boy and alien go trick-or-treating, boy helps alien phone home) you still won’t have enough detail to really ‘know’ the core of your story. A first draft can get by without every last tidbit that will go into the final story, but it does need enough detail to flesh out the story. Without that detail, all you have is an outline. Outlines can be helpful, but the thing about them is that they’re a plan, while a story is execution. Even the most detailed plan goes astray when you get to the point of actually putting it into action. An outline is like Xs and Os on a coach’s clipboard; a first draft is like an actual practice with the full squad. As soon as you see your plan in action, you’ll be changing it, because the act of fleshing it out will push it in directions that you didn’t foresee.

Third, you need—well, you really don’t need anything else. If you write a beginning and ending with enough detail to tell the story, then you have a workable first draft. More specifically, here are some of the things you can skip in a first draft:

A middle

Okay, you can’t actually skip having the middle of a story. Every story will technically have a middle that ties together the beginning and ending, even if it’s just the phrase ‘and then.’ But you don’t need a good middle in order to have a first draft. You don’t need all of the various plots and characters that will eventually go into your story. You don’t need all of the scenes that will stretch out the pacing so that the reader has enough time to anticipate and enjoy the ending. All you really need in a first draft is enough connective tissue to lead the story from your beginning to your ending. When you’re in the middle of your middle, that’s the time to make sure you keep your momentum up. Beginnings are easy, since there’s so much possibility. Endings are easy, too, once you have an idea for what they’ll be, since the pressure of the story is pushing toward that last chapter. But middles are like endothermic reactions: you have to add energy to keep them going. So focus on keeping up that momentum and keep the words flowing. There will be plenty of time later to tighten things up and add all the bits you skip.

Continuity

Oh, boy, is this something you don’t need. Worrying about continuity in a first draft is like worrying about your kid’s college fund when you or your partner are in labor. If something changes halfway through your draft, let it change. Jot it down somewhere if you want, but keep going. Nobody is going to read this draft except you, remember?

Setting

Like the middle, a setting is something you can’t really get away from. But you don’t need a fleshed-out setting. In fact, I believe that you should actively try to not flesh out your setting until you’ve finished that first draft. You’ll probably have at least something of the setting in mind when you start, and that’s great. But don’t spend any time at all at world-building (meaning, the process of expanding that notional setting into something that feels real and believable) until later. In your second, or third, or tenth draft, it may be very helpful to know a million different details about your world, but before you write that first draft, how do you know which million details you need? And what happens when you get halfway through and realize that you need your castle to be next to a river, except that your well-fleshed-out world has your castle sitting in the middle of a desert? There will be time for world-building, but the story has to come first. By all means, include whatever details you already have, or which come naturally while you’re writing, but don’t spend a millisecond actively trying to build your world until you have (at least) one draft of your story written.

Prose

Uh. This one may be a bit of a puzzler. How can you write a story without using prose?

Well, playwrights and screenwriters (screenwrights?) do it all the time. Their format is nice and simple: dialogue, centered on the page with the speaker’s name on the line above, and stage direction or screen direction in blocks where necessary.

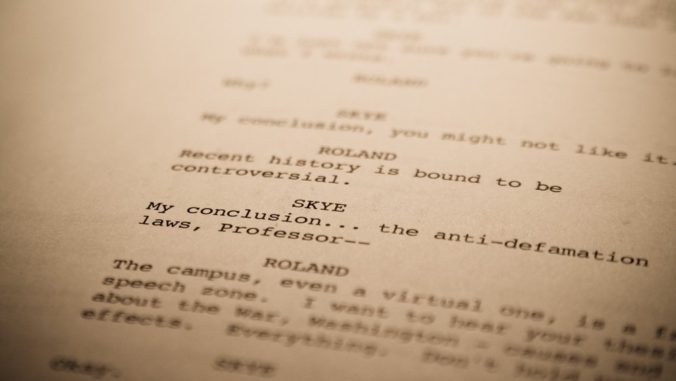

Is it helpful to write out the first draft of a novel as a screenplay? I think it can be. Not as a full screenplay format, but something closer to a script treatment, which is sort of a film industry rough draft. The nice thing about the script treatment format is that it’s clearly not your final draft, so there’s much less pressure to get any part of it right. You still have your dialogue, which is one of the most important bits of a first draft, and you have the major action. You can include as much incidental action as you want, but you get to do it in a nice shorthand format. Here’s a section of a science-fiction novel I’ve been working on:

The cargo doors open up, revealing the Atlantis about a hundred meters away, framed against the blackness of space.

RAHUL

This is as close as you can get?

LUCAS

Just get yourself in position and jump. Don't overdo it.

RAHUL

What if I miss?

ELENA

Don't miss.

Elena goes first, and to no one's surprise, lands gracefully at the waist airlock. Addy goes second and manages okay. Rahul somehow manages to put himself in a slow tumble, and Elena has to catch him. She waves at Lucas, who then jumps over easily.

The nice thing about this format is that I can write much more quickly than if I write ‘real’ prose. The bits of action are written as notes to myself, which lets me be as detailed or un-detailed as I want. Whatever I have, I put in; whatever I don’t, I leave out. One of the things I really hate is when I know I need to move to the next scene, but I don’t have a clear way to ‘get there.’ With this format, I just stop where I am and start the next scene, and leave the connecting prose to a later draft.

If you want a great example of a script treatment, you can read James Cameron’s treatment for The Terminator here. Cameron does a great job of telling the core of his story in the most simple and straightforward way possible. If you look closely, there are details and bits that an actual shooting script would require, but at the same time, the story is all there, right on the page.

The downside of this format is that you haven’t actually written your prose yet, and that’s something you’re eventually going to have to do. But for me, a first draft is often so rough that I can hardly keep any of the text, anyway, so using a completely placeholder format doesn’t end up wasting much time.

Quality

Out of all of the things that a first draft doesn’t need, this is the biggie. Nobody is going to read this draft but you. Tell yourself that, over and over, while you write. It can suck. It can leave bits out. It can be a barely-functioning, on-life-support story, but as long as it’s a story with a beginning and end, and as long as it has enough detail to prove out the novel that it will become, then it’s a first draft.

The flip side to this mode of thinking is that eventually, you do have to care about quality. Your story will require a middle, and prose, and setting. All of those things will have to be developed. If you’re the sort of writer who can rattle off all of those things in a first draft, then god bless you. For the rest of us mere mortals, figuring out which parts you can leave out is one of the major keys to finishing that first draft.

from the missing-pieces-in-a-jigsaw dept.

Leave a Reply