Writing is hard.

Boy, howdy, is it hard. There are a million things you need to learn if you want to master the craft. There’s big, story-level stuff like character arcs, plotting, theme, and pacing. There’s small, line-level skills like writing clearly, using proper grammar, and not overusing your favorite part of speech (whether that’s adjectives, adverbs, or participle phrases).

But really, there are only three basic steps to becoming an accomplished writer. (And two of them are the same thing.)

Don’t believe me? Here they are.

Step One: Write something as well as you can

“Oh, is that all?” you might say. “Just write well?” Except I’m not saying you need to write something at any particular level—just that you write it as well as you can. It doesn’t have to be David Copperfield. It doesn’t have to be anything other than the best you can do.

It’s still easier said than done! Writing something to the best of your ability means not putting up with anything less than your best. It means taking everything you’ve learned so far and applying it to the entire story. It means rewriting sketchy passages until they’re as polished as you can make them. It means trying to get your characters as human as you know how to make them. It means making it your very best.

It also means finishing. Not just finishing the first draft (and aye, that’s hard enough) but taking the time to clean it up so that it’s consistent. It means not stopping with your rewrites until there are no areas that you know how to make better.

I know this seems blindingly obvious, but it’s important. You can only fix problems that you know how to fix. Furthermore, you won’t know how to fix every problem until you’ve mastered the craft (and maybe not even then). You have to force yourself to solve the problems you know how to solve, while also not beating yourself up about the problems you don’t know how to solve.

Curtis Sittenfeld said it much better than I can:

“It’s OK to let your book be [finished] if you can see its flaws but don’t know how to fix them. Don’t let your book be [finished] if it still contains flaws that are fixable, even if fixing them is a lot of work.”

I’m paraphrasing, here, since she wrote “published” instead of “finished,” but the same principle applies.

So you’ve completed step one! Congratulations. You’ve written something that you can justifiably be proud of, whether it’s your first time at the keyboard or whether this is your tenth novel in ten years. You’ve looked it over and found no problems that you know how to fix. What do you do now?

Step Two: Learn how to make it better

You figure out some of those problems you don’t know how to fix. You figure out how to make it even better.

Once again, this is easier said than done. Didn’t you just write this to the best of your ability? Didn’t you stop precisely because you couldn’t make it any better? Well, yeah. Except you know that it can get better, in a hundred different ways. You just don’t know precise solutions yet. And it’s now your job to figure some of those out.

The first thing you need to do is set it aside for a few months. When you come back to it, you’ll have a much more objective eye, and poorly-written passages will stand out like sore thumbs. Or a particular plot arc (one that you were so proud of) will make you roll your eyes.

But in the meantime, you need to get help from other people. Read books, attend classes, go to conferences and seminars. Ingest their advice like an elixir of learning and store it in your belly. Take notes, highlight, bookmark, record. When you go back to your manuscript, take your notes and see how they apply to your story. You’ll likely find a half-dozen ways to use the advice to improve your manuscript.

Even better: get people to read your story! Preferably, get critiques from other writers who are at least as accomplished as you are. There are a lot of online critique groups which will help you do exactly this. Your fellow writers will helpfully (and constructively) point out a dozen more major things you can do to improve your story. Remember, though, that it’s their job to convince you of things that need to change. You’re not looking for someone to hand down edits from on high. You’re looking for someone to show you what things aren’t working and suggest fixes. Most of the time, you won’t take their fixes exactly as suggested. But their suggestions will spark ideas of your own for how to improve the piece. And more importantly, their feedback will help you understand how to write better, meaning that even if you never actually go back and revise this particular manuscript, you’ve still advanced your knowledge of the craft.

Which brings us to the final (?) step…

Step Three: Do it again

In Step One, you worked on your manuscript until there were no problems left that you knew how to solve. In Step Two, you spent months learning how to fix things that you suspected were broken and finding out about new types of problems that you didn’t even know existed.

Now you put that knowledge to use by looping back around and writing again.

It doesn’t have to be the same manuscript. It’s up to you whether you spend time improving something you’ve already written versus starting on a new project. Sometimes you’ll spend months learning and yet still feel like there’s no specific way to improve the manuscript you’ve just finished. In that case, move on! Start something new.

But a lot of the time, you’ll come back to that manuscript with a mental list of the things you can do better. It’s almost like those daydreams you have about how much better you could do high school if you could do it all over again. (Everyone has those daydreams, right?) You’ve gained wisdom. You’ve gained confidence. You’ve leveled up.

And so whether you start a new project or rewrite an old one for the umpteenth time, you’re writing better. That’s the only thing that matters.

When you look back at something you wrote ten years ago, what’s your first thought? I’ll bet it’s oh, man, I can do so much better than this now. That’s the one-and-only sign of becoming an accomplished writer. There’s no reliable way to measure yourself in any absolute sense. But you can certainly measure yourself relative to your skill in the past. And if that writing you see in your rearview mirror always makes you scream holy cow I’m better than that, then you’re learning your craft.

To put it another way, it doesn’t matter where you are as a writer right now. The only thing that matters is your trajectory. If you’re improving, and you keep working at it, you’ll keep improving. You’re upward-bound. Think of it like this: would you rather have $100 now, or $10 per year for twenty years? Growth is the thing that matters, not your current skill. If you keep growing as a writer, you will eventually achieve your goals. Full stop.

I freely admit that I’ve glossed over nearly all of the important details about writing. This advice, on its own, is almost useless. You’ll need to study and follow the guidance of writers who are much better than I am if you’re going to actually accomplish any of this.

And yet.

That advice can be overwhelming, frustrating, and painful, because you can’t always follow it. You’ll pore over a book on writing better dialogue, and then you’ll apply it, and you’ll say wow I still screwed that up. It takes a long, long time to learn everything there is to know about even a small part of the craft of writing.

But you can always follow these three steps. Nothing can ever stop you. Write, improve, write again. When everything else seems bleak, you can look back and know that you’ve learned something new and put that knowledge to use. If you keep following that path, you’ll always get where you want to go.

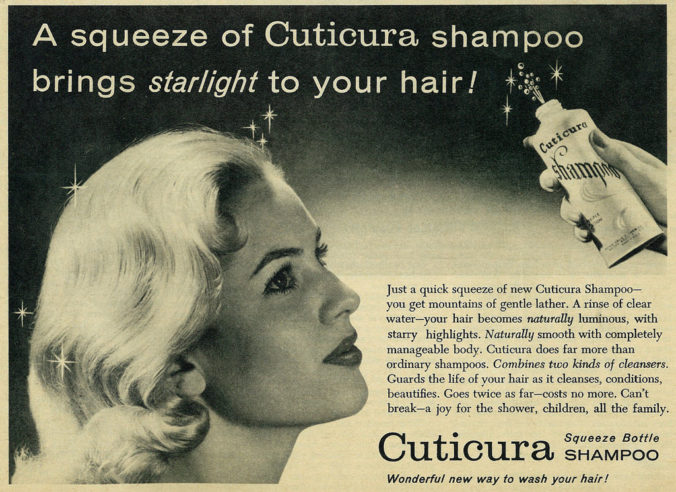

from the lather-rinse-repeat-dept